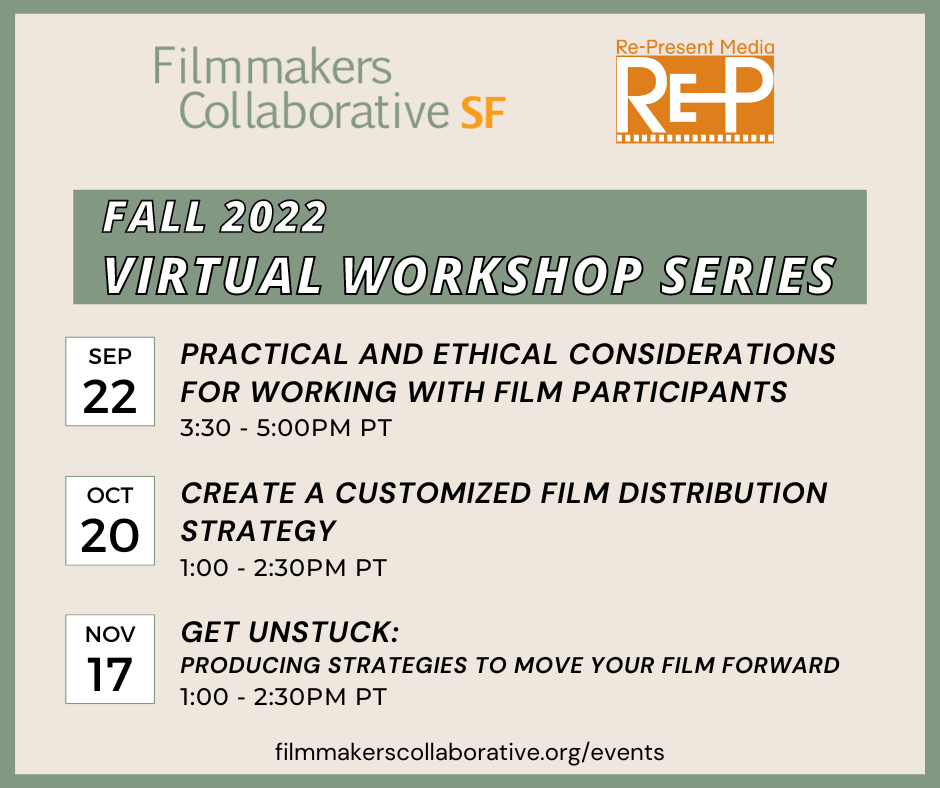

Filmmakers Collaborative SF and Re-Present Media are presenting a series of workshops focused on helping filmmakers with practical filmmaking advice and strategies to move their films forward. Workshop participants will walk away with tangible documents and tools for the next step in their filmmaking journey.

Practical and Ethical Considerations for Working with Film Participants

Thu, September 22, 2022 | 3:30pm – 5:00pm PT

This practical workshop aims to equip filmmakers, funders, and participants to address challenges that arise during the filmmaking process by highlighting existing tools and resources on documentary ethics and accountability. It will focus on financial impacts and benefits, ownership, content review rights, and the film’s impact on participants.

Create A Customized Film Distribution Strategy

Thu, October 20, 2022 | 1:00pm – 2:30 pm PT

This hands-on workshop will help filmmakers design a customized distribution plan for their film. We will cover creating goals for your film, evaluating different distribution channels, finding audience, strategies for DIY distribution, sequencing your release, and more – all with the goal of creating a unique and actionable distribution strategy for your film.

Get Unstuck: Producing Strategies to Move Your Film Forward

Thu, November 17, 2022 | 1:00pm – 2:30pm PT

This hands-on workshop will help you critically assess your ideas, structure development and strategy to successfully secure funding and move your film forward. It will focus on aligning the filmmaking process with a film’s funding potential, efficiently organizing time and resources, producing a compelling work sample, proposal and pitch deck, leveraging a team approach, and more.

Cost: Free for Filmmakers Collaborative SF members or sliding scale (pay what you can)

For more information and tickets, visit: https://www.filmmakerscollaborative.org/events